Over the last few decades, the scope of medical education has broadened to align more with current patient needs. Developing expertise in the physical sciences and knowing how to treat a patient remain crucial but are no longer the sole factors to address larger, systemic problems within U.S. healthcare.

Many medical educators and residency programs have developed holistic programs to provide quality improvement training in the form of hands-on research projects and electives to measure and improve care processes. This is turn, ultimately improves care delivery and patient outcomes.

Moreover, some of the most comprehensive quality improvement programs now supplement traditional medical education with in-depth training in skills like data management, leadership, and quality improvement methodologies. The aim is to ingrain behavioral habits within residents to constantly think big-picture on shortcomings within the existing healthcare system.

As discussions around Social Determinants of Health continue to gain momentum and promise to fundamentally change the way we approach healthcare, testing the role of quality improvement in research-driven healthcare organizations for new models of care delivery is an interesting, emerging consideration.

In order to affect large scale change within a broken healthcare system, building proven and data-driven models will be an important first step to set a precedent that can be replicated.

The Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, an Academic Medical Center (AMC) with quality improvement training, offers a program in which residents must identify specific patient populations, exploring the current processes and observing gaps that exist within provided care and patient outcomes. Another example is the Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality within Johns Hopkins Medicine, which places an emphasis on projects that improve patient outcomes and decrease healthcare costs by rigorously following the scientific method and collecting data to evaluate and build on successful models. Armed with funding, powerful research tools and a firsthand perspective of patient populations, it comes as no surprise that many of the ideas and initiatives that have been generated from AMCs have been both effective and innovative in addressing outstanding issues such as social determinants and health inequities.

As an example of a well-documented health inequity, food insecurity – defined by the U.S Department of Agriculture (USDA) as the disruption of food intake and eating patterns due to a lack of money and resources – affects an alarming 14.3 percent of U.S households. In a novel approach to address this issue, Patricia A. Carney, a professor at the OHSU (Oregon Health & Science University) School of Medicine, directed a program that assisted farm workers to mitigate their food insecurity by growing home gardens.

The results that followed were nothing short of astounding: the frequency of participants eating vegetables several times a day jumped from 18.2 percent to 84.8 percent, while the frequency of participants worrying about food running out due to a lack of money dropped from 31.2 to 3.1 percent.

Another similar effort being carried out by the UCSF (University of California, San Francisco) to address food insecurity is the creation of the San Francisco General Hospital Therapeutic Food Pantry. Through this program, patients can get prescriptions filled for healthy foods in an analogous manner to obtaining prescriptions for pills and drugs that can be picked up at the pharmacy. With an estimated 26,000 patient counters in the first year of service, the pantry’s ultimate goal is to measurably improve health outcomes through markers such as blood pressure and weight. With such promising initiatives that are addressing healthcare in a much broader sense, the value of data-driven models and emphasis on quality is undeniable.

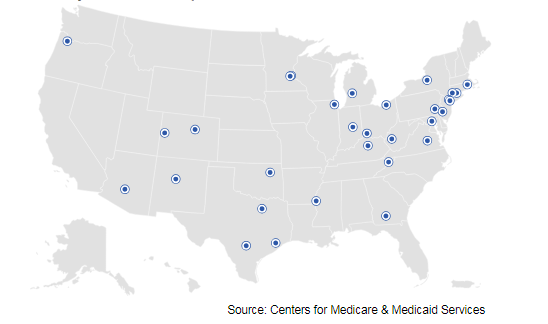

Even large government bodies outside academia such as the CMS (Centre for Medicare & Medicaid Services) have recently begun exploratory research-based quality improvement programs such as the Accountable Health Communities Model.

Through this initiative, healthcare institutions across the country are now collecting concrete data on the gap between clinical care and local communities by screening Medicare and Medicaid patients for unmet health-related social needs and analyzing community services and locally available resources to meet these needs.

In what will undoubtedly be a trend to keep a close eye on, these programs and initiatives mark a tremendous step forward to evaluate new models that can remove current barriers in the system and sustainably move healthcare forward.