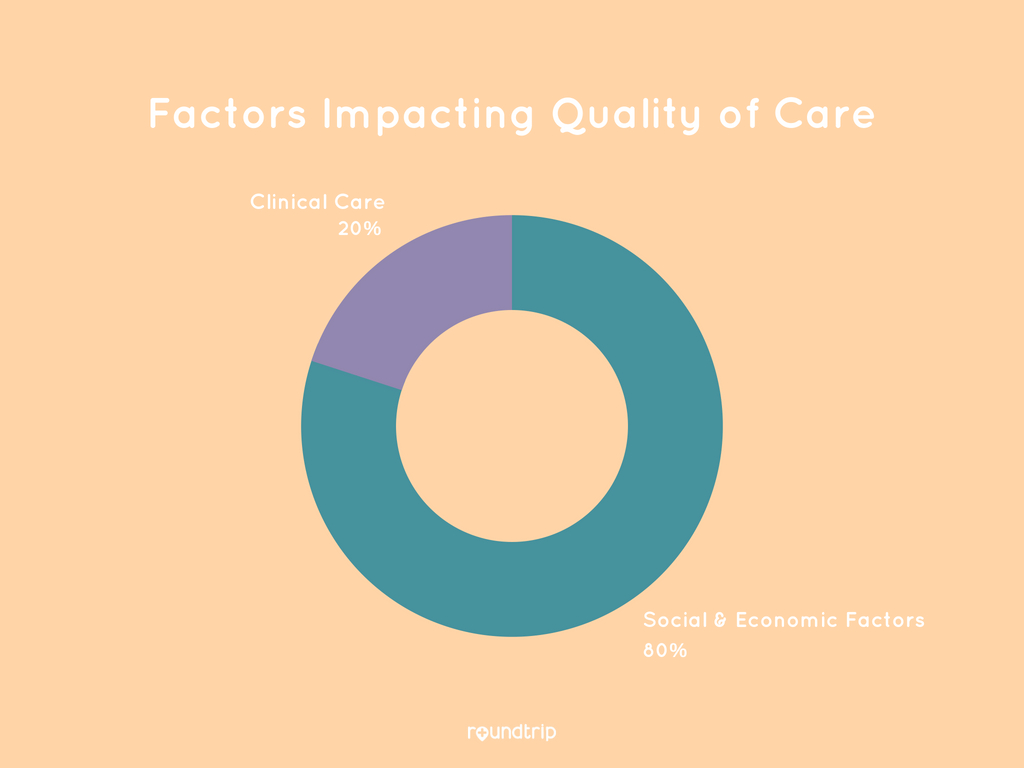

When it comes to our well-being, it is easy to assume that the quality of our medical care plays the most significant role. Research says otherwise. In fact, clinical care has been shown to account for only 20% of our health. The staggering 80% that remains is accounted for by social and economic factors including our behaviors and physical environment or social determinants of health (SDOH). The ways in which we are able to live life outside the hospital, including the resources we have access to, have the greatest impact on our health.

In May 2018, a Leavitt Partners U.S physician survey on understanding attitudes towards SDOH showed that while most physicians believe that SDOH largely influence their patients’ general health, physicians also believe they should not be responsible in addressing SDOH. At first glance, these two findings seem to be at odds with one another. After all, why would primary care givers intentionally neglect what they themselves deem as important when it comes to the health of their patients?

Why SDOH Impacts Quality of Care

The answer lies in the inefficiencies of our current healthcare system, in which the lives of physicians are fatigued with burnout and administrative burden. The truth is that the average physician today simply does not have the energy, experience, or the proper incentive to address healthcare determinants that fall outside the umbrella of the clinical setting. Among the three main SDOH that were highlighted in the survey – information about the price of care, information about health insurance, and help coordinating transportation – the last stands out both in its significance and lack of accountability. 66% of the surveyed physicians indicated that help arranging for transportation would help their patients to a great or moderate extent, but almost 70% simultaneously expressed that the doctor should not be held responsible.

In a broader context, hospitals and healthcare systems have often turned their backs on transportation, according to a November 2017 report published by the American Heart Association. The prevailing concept has always been that the core focus of a healthcare facility is in care delivery, and the burden is on the patient to make the journey to receive the care. Given this lack of transportation ownership, it is no wonder that the healthcare transportation system is broken.

The following three statistics illustrate the grim situation that we see today:

- An estimated 3.6 million appointments are missed or delayed each year due to transportation issues

- Missed medical appointments are a $150 billion burden on the healthcare system

- Transportation is the 3rd most commonly cited barrier to accessing health services for older adults

Transportation barriers significantly affect an individual’s access to obtain medical care and can result in increased health expenditures and poorer health outcomes. Additionally, 65% of patients say that transportation assistance would aid with pharmacy access and prescription refills, indicating the sad reality that many succumb to health problems because of the inability to obtain medication they have already been prescribed.

Furthermore, studies have even shown that transportation is strongly interrelated with other SDOH including poverty, social isolation, access to education and racial discrimination. A lack of adequate transportation to grocery stores, for instance, is a large cause of food insecurity, resulting in minimal consumption of healthy foods on a daily basis. Undoubtedly, the problem is widespread, and the best course of action is to treat the cause: to remove transportation as a barrier to well-being. However, any means to do so first begs the question: Who is responsible?

Who is responsible for addressing transportation barriers

To answer this seemingly complex question, we must turn to the financial impact of the betterment of transportation. In a study conducted at Florida State University regarding the cost-effectiveness of Florida’s NEMT (Non-Emergency Medical Transportation) program, it was found that every dollar invested in NEMT saved approximately $11 to the State. This ROI was based on conservative estimates of the number of avoided hospitalizations and admissions, as immediate access to transportation creates healthier citizens and eliminates the financial burden of treating worsened health outcomes.

As a result of studies like these that showcase the economic return of investing in SDOH such as transportation, many stakeholders within the healthcare space are slowly taking notice. From hospitals that are piloting new transportation programs to health plans that are changing policies towards providing transport benefits, there is a growing consensus that addressing socio-economic barriers such as transportation is necessary for all the stakeholders involved. When a single patient is unable to find or pay for a ride, the accumulated costs affect caregivers, providers, employers, insurers, and even taxpayers. The entire healthcare system loses revenue from missed appointments because of the downstream effects on delivery, cost of care, and resource allocation.

Thus, the responsibility does not fall to a singular entity, but to the system at large. In order to fully address transportation and other SDOH, collaboration is necessary not only among hospitals, health systems, and health plans but also governmental agencies and communities, who are equally invested in the health of the population and incentivized towards its improvement.

Finally, with the advent of digital health and technology platforms, there is a strong pull for the private sector to innovate and supplement the existing resources of healthcare organizations with the operational streamlining and data transparency that technology affords. Ultimately, SDOH are inextricably linked to our health, and it is our collective duty to ensure that factors like transportation are a stepping stone towards societal well-being rather than a roadblock to our progress.